This post is also available on my Substack, here.

I woke up at 9.30am today, the First Sunday in Advent, and I was too late to make it to church. And there was a moment there where I got truly, irrationally angry.

Not with churches. With Advent.

The season of waiting… and waiting… and waiting.

In a world dying from injustice.

How Long, O Lord? Barriers to Sunday Services

I’m on new medication, and I’m burned out. My sleep is a mess. That means one more barrier in the way of getting to church – as if I wasn’t already facing enough of those.

I’m not the only disabled person who struggles with getting up for services, as my research on disabled people’s experiences in churches found. In a 5-mile radius from me, there is one church with an evening service – and it’s a church that does not welcome LGBTQ+ people (like me). At the few churches with services that start later than 10, finding parking is the next barrier. Then step-free access. Ideally, I’d also like my church to have a theology of disability that doesn’t mean people insist on praying for my cure. I’d love a church with occasional services that are more contemplative and less wordy, where the community is more accessible for my neurodivergent ways of being… But at this point in the list, I’m dreaming of the kind of access that I don’t realistically think I’ll ever find in one place.

So for now, I’m just longing for a nearby evening service.

Waiting.

In a world where disabled people are facing serious, life-or-death injustices, it might seem insignificant to lament barriers to church. But my disabled life means I’m often isolated, often lonely. It’s painful when I can’t access community in either of my spiritual traditions. Because of factors in my life… and because of the choices these communities make.

“How long, oh Lord? Will you forget me forever?”

― Psalm 13:1

Activism and Burnout

(Topic change alert – but I promise it’s about to be relevant to the idea of waiting for justice…)

Autistic burnout is not uncommon.1 If I can catch myself early enough in burnout, I can usually head it off before it gets really bad (and I can no longer speak or interact with people). If I can rest.2

Except… that there’s work to be done. And in the ableist society we live in, it’s work that needs doing.

How can I stop and rest now, in a society where the government is declaring war on benefit claimants, again; where 4.7 million disabled people live in poverty – including 600,000 children – and diseases we thought we left behind with the Victorians are returning?

How can I stop working now, when MPs have just voted in favour of assisted dying, in a country where there is very little assistance for disabled people to live?

In an unjust world like this, how does stopping help anyone?

If I let myself dig deeper, there might be darker thoughts motivating all this activity.

If I don’t do this work, who will?

The idea that I have to do all the work for justice, or it won’t happen, is an expression of pride. It’s how the lies of toxic productivity culture sneak into our work for justice. Our neoliberal society might think powerful individuals create change, but disabled activist communities know better. Rejecting the pressure to be the ‘sole solution’ is a powerful act of resistance. Disability justice is about community.

“It’s not about self-care – it’s about collective care. Collective care means shifting our organizations to be ones where people feel fine if they get sick, cry, have needs… where there’s food at meetings, people work from home – and these aren’t things we apologize for.”

― Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice

And that means our communities need to support each other to rest.

Rest as Community Resistance

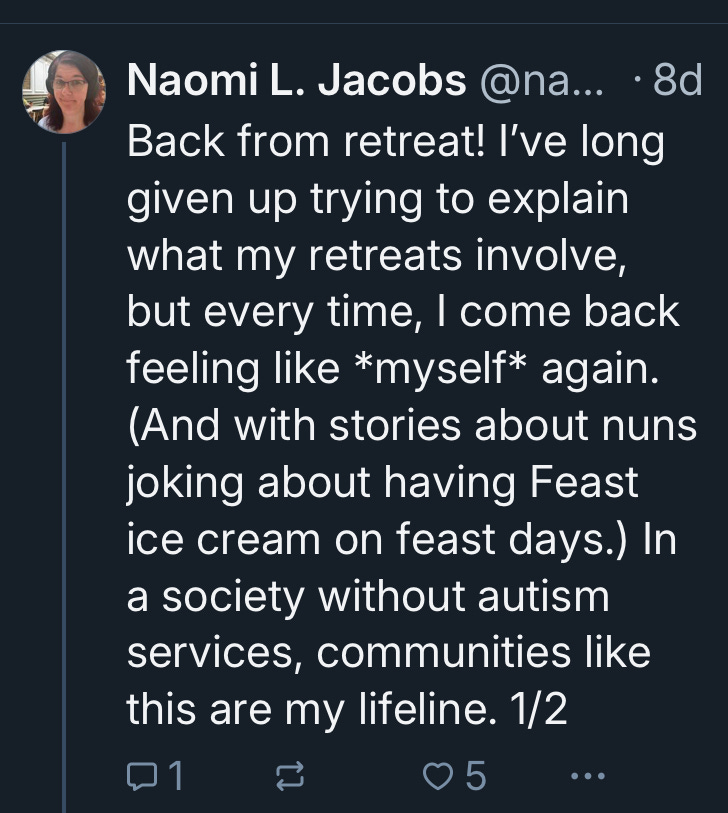

I went away on retreat a couple of weeks ago. I stayed with a beautiful, welcoming community of nuns. I spent most of the time in silence (if anyone who’s met me can believe that) – mostly alone, sometimes with the community. I had a complete break from my overwhelming daily reality.

That can be literally life-saving:

I’ll leave aside the question of whether it’s right that religious communities pick up the slack, in a society where health and social care systems are collapsing – that’s a subject for another time. For now, I’m just grateful this community is there, and that I managed to rest for a few days. And only because these sisters’ lives are dedicated to being a community of care3 with those around them.

I’ve been thinking about what community-enabled rest looks like, as modelled by that particular community of care – and many others:

- It’s when my disabled friends text, or comment on my posts about working too hard, reminding me to rest, because I matter. (They do this a lot. 🤍)

- It’s when researchers share plain English research summaries, so that everyone can access knowledge to empower their activism, without extra work.

- It’s when some churches are still streaming their services, often despite having few resources to do it – giving disabled people access from bed.

- It’s when crip friends help me when my partner (and full-time carer) is away, even though the friends in question have very little support themselves.

- It’s when disabled leaders share their wisdom in online sessions that everyone can join. (In contrast with my university, where the growing number of ‘in person only’ events is justified by nonsense about the importance of being ‘face to face’ – as though that’s the only way to be in community with each other.)

- It’s when a community opens its doors, in a world where so many people have access to so little, and share what they have. (This article made me wonder if churches could start sharing their kitchens with families in substandard housing.)

I’m not someone who has much community around me, physically. That makes me even more grateful for my together-at-a-distance disabled friends, and all the ways we act as communities of care for other. Including supporting each other to rest.

“As a sick and disabled, working-class, brown femme, I wouldn’t be alive without communities of care, and neither would most people I love… We do this because we love each other, and because we often have a sacred trust not to forget about each other.”

― Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice

Rest As Resistance to Injustice

It’s in these communities of rest that we see a glimpse of what Black author Tricia Hersey calls rest as resistance – against society’s dehumanising values of overwork:

“Rest is a form of resistance because it disrupts and pushes back against capitalism and white supremacy. Both these toxic systems refuse to see the inherent divinity in human beings and have used bodies as a tool for production, evil, and destruction for centuries.”

― Tricia Hersey, Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto

Last week I joined an online session with the Diocese of London, where the fantastic Rabbi Julia Watts Belser was sharing her Jewish tradition of Sabbath rest. She led us in reflecting on Exodus 5. That’s the bit where Moses asks Pharaoh to let his people take time off work for a religious festival, and the people are punished for it – made to work harder. How dare the workers ask for rest? “They are lazy,” as verse 8 has Pharaoh saying. (Sound familiar?)

There are ableist forces at work when we push ourselves to just keep working. Julia wondered if these become our inner Pharaohs, telling us us we’re lazy, warning us we’ll be punished for resting. The internalised ableism lurking in the belief that I am worth nothing unless I am productive. The external ableism in workplaces – academic ableism is a reality – and how disabled people worry that we could lose our jobs if other people notice we’re disabled… so we just keep working, even when we’re ill.

And I thought about the all-pervasive fear – after 14 years of austerity from UK governments, amplified in the media – that our benefits could be taken away, that we could be left utterly destitute, because we have committed the sin of not being economically productive enough. How dare they ask for rest? Look how lazy they are!

Choosing rest can be a powerful way to say ‘no’ to ableist capitalist culture and the toxic productivity it seeds, where our worth is measured by how much we can work:

“Some of us need rest; some of us contend with pain; some of us know that all the support in the world isn’t going to put a paycheck within reach. Ableist assumptions turn those realities into a referendum on our worth. What’s the first thing most of us ask each other when we’re first introduced? ‘What do you do?’”

― Julia Watts Belser, Loving Our Own Bones: Rethinking Disability in an Ableist World

But this is not an easy form of resistance. Maybe that’s why so many of us end up in burnout. I don’t think burnout is ‘just’ about being autistic, for me – although autistic people are more susceptible to burnout because of the daily stress of life in a neuronormative society. But we’re all at risk from the harms of toxic productivity culture, in this society that prioritises work above wellbeing.

At the root of burnout, at least for me, is fear.

Advent: I’m Still Afraid

I’ve just started reading Rachel Mann’s Advent book, Do Not Be Afraid: The Joy of Waiting in a Time of Fear. If I’m not good at resting, I’m really not good at waiting. When the psalmist said, “How long, O Lord?” he probably wasn’t expecting God to answer, “About another thousand years, give or take.” He probably wanted justice now.

“Those who long for change and justice in a world on fire and in a Church in meltdown can be left feeling as if the very idea of waiting is not only exhausting and irritating, but deeply offensive.”

― Rachel Mann, Do Not Be Afraid: The Joy of Waiting in a Time of Fear

The season of Advent is about waiting. It’s about hope in the waiting. Like Mary’s celebration of justice, after the angel announces the coming of Christ:

“He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty.”

― Luke 1: 52-53 (The ‘Magnificat’)

It’s a wonderful statement of hope. We repeat it every day, in my tradition. And every day, I look around, and I don’t see the justice Mary spoke of in the world around me.

I’m still afraid.

I’m afraid of living in a country where finding assistance to die may soon become easier than finding assistance to live, to quote Disability Rights UK. I’m afraid of a society where disabled people are dehumanised and devalued: where most of us cannot access social care, where there are massive extra costs to being disabled, and where our country is failing to improve on the “grave and systemic violations” of disabled people’s human rights that a UNCRDP investigation first found in 2016. I’m afraid of a world where climate change, war, global poverty and health inequalities impact disabled people globally, long before the privileged take notice.

And I’m afraid of a church that – I fear – doesn’t value disabled people. Even in the midst of the bright spots I find on the edge, from disabled-led Christian groups, to religious communities of nuns with a mission of hospitality. In its silence and inaction about disability injustice, the church (still) tells me it doesn’t really care.

The temptation is to keep on doing, to keep on working, in the hope that my individual effort will create change. But maybe it won’t. Maybe I need to get used to waiting. That doesn’t mean activism isn’t important – it might never have been so important, in my living memory. But I am one tiny person, and there is an end to what I can do.

And at the end, in the silence and emptiness of defeat, when I know I can’t do anything more, something new might be taking root.

I’ve written before about how Christians have a tendency to rush from Good Friday to the triumphant moment of Easter Sunday, without waiting for a moment in the fear and trepidation of Holy Saturday, where so many of us marginalised folks live. I think a lot of us live in Advent, too. We’re still waiting for the justice Mary sang about. I’d love to join in with the church’s hope-heavy celebration of Advent, as they look forward to the Kingdom of God, where justice will roll down like a river and everything will be great and we’ll get there any minute now. I’d love to linger on hope.

But I think you’ll probably find me in the waiting.

Thank God for the communities of rest and resistance who wait with me.

“Advent offers a holy opportunity to wait on the one who stands in solidarity with us; the one who calls all of us… into the fullness of life.”

― Rachel Mann, Do Not Be Afraid: The Joy of Waiting in a Time of Fear

Another great book on waiting is Those Who Wait: Finding God in Disappointment, Doubt and Delay, by disabled theologian Tanya Marlow.

Rachel Mann is speaking about her book from St James’ Church, Piccadilly on 5th December, as part of the church’s celebration of Disability History Month. The church is also holding an exhibition of disabled artist Nancy Willis’s work till 8th December.

- We don’t know quite how common yet, but there’s growing evidence about what burnout looks like for autistic people – there are lots of studies, but here’s one more. ↩︎

- Getting rest can be complicated for A(u)DHDers, because – at least as it has been explained it to me – we need a lot of active rest. Our rest doesn’t always look like other people’s, and that’s okay. But it can hard for some of us to work out what it does look like. ↩︎

- A phrase used by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha in Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. ↩︎

Recent Comments